The green Ireland is land of pain and succeed, of legends and feeric beings. Its people carry the essence of their land wherever they go, often forced to leave it by the socio-political-economic circumstances of the moment. Its majestic architecture fused with extensive green meadows and steep cliffs has inspired a multitude of writers, scientists and artists of all kinds. Their music, sports and products have spread all over the world and their influence can be found unsuspectedly in many fields. All that and more is Ireland. With this first article we open a new section in Periérgeia and give rise to a series of entries in which we will tell our experiences in those magical lands. We hope to achieve our goal: that the reader falls in love and feels the need to travel to the Emerald Isle.

Our planet, that fundamentally blue stain that roams the universe, is home to a rich variety of places that delight human senses, which often need the contemplation of beauty as a stimulus. The wonders that dot the surface of our blue orb, whether human-made or not, are (or should be) an irreplaceable food. Unfortunately, we need more than one life to enjoy them all thoroughly. Even so, in Periérgeia we want to face this challenge and make known these places to induce the reader to travel and corroborate with their own experience if what we say in this section is true or not. “The Magic Planet” is how we have called this section, where we will share with all of you that magic that filters through the fractures of the ruins, through the ashlars of ancestral constructions, through the rose windows of cathedrals and churches, through the branches of trees and the rocks of cliffs and mountains. This magic is available to everyone… We only have to reconfigure the senses and acquire that sensibility that allows the access to those subtle energies and to the mystical connection with the beauty that has aspired to be eternal.

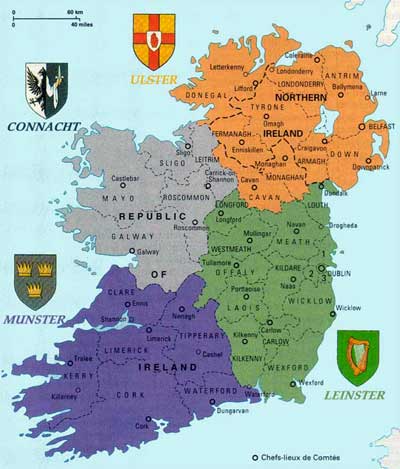

The first stop on our journey through the magical planet is an island that has belonged over the centuries to a heterogeneous variety of cultures and ethnicities that have had their more and their less among themselves. A place that has suffered profoundly unjust punishments and inhuman slavery and that has inevitably hardened the survivors. Our first stop is therefore Ireland, the nineteenth largest island in the world. Placing it on a map is simple: it is in the North Atlantic, to the west of Great Britain, separated by a strait from it. To avoid confusion, when we speak of Ireland we are referring to the island as a whole, because our journey has taken us through the two political regions that divide the island: Northern Ireland, belonging to the British crown and whose capital is Belfast, and the Republic of Ireland, whose capital is Dublin. At certain times, however, we will be obliged to make the relevant distinction. Geomorphologically we cannot make an unitary analysis, because of the great diversity of landscapes the island has. Even so, it is worth highlighting the imposing cliffs that, as magnificent fortresses protect the southern, northern and western fronts against the inclemency of the furious Atlantic, while in the eastern margin the beaches and the sandy dunes have more room. The center of the island is governed by a mountainous plain profusely covered by deposits left by ancient glaciers and is dotted by several lakes and swamps. Dozens of rivers run through the heterogeneous Irish surface, the longest being the Shannon River. Other notable rivers would be the Blackwater or the Liffey river, which crosses the center of Dublin. Because it is surrounded by the Atlantic and the proximity of the Gulf Stream, the island enjoys a temperate and humid climate and there are usually no major thermal shocks. Its poetic nickname, the Emerald Island, is due to its conspicuous greenery, given in turn by the abundant rainfall. The pleasant summer temperatures and the not so cold winter help to enjoy its landscapes at any time of the year.

Ireland is currently divided into four provinces: Connacht, Leinster, Munster and Ulster. Its origins are lost in medieval times, when the Irish territory was divided into even more kingdoms. The capital of the republic, Dublin, is located in Leinster, whose provincial flag is recognized by many thanks to a famous brand of beer that was born there, in Dublin: the Irish beer Guinness, which also carries the golden harp in its bottles and merchandising.

Our arrival at Dublin was calm and without a hitch. We were greeted by a rather benign climate, with a few clouds plowing through the sky and a radiant sun, refuting our fears of encountering an unkind climate. As in any big airport, people filled up the facilities. As soon as we landed, we contracted a very useful transport pass that would allow us to travel by bus, in DART (Dublin Area Rapid Transit; that’s how they call the Irish train) and in Luas (the tram). We recommend any traveler visiting Ireland to purchase this (Leap Visitor card) or another alternative to move freely around Ireland and save some money. There was not much to highlight about the airport, as its appearance does not differ too much from that of any other airport. Its history is interesting however. It began to offer civil service in the middle of the Second World War: on January 19, 1940 it offered his first flight to Liverpool. At that time the airline Aer Lingus was also born, which is so widely used today. It seems unbelievable that in the 1940s it only offered flights to Liverpool and, occasionally, to Manchester. From then on, more air connections began to emerge. However, before 1940 it was used as a military base by the British Royal Air Force until it fell into disuse. Several important people have stepped on its soil, such as John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Pope John Paul II, members of the Beatles, etc..

After catching a bus at a Terminal 1 stop, we went to Dublin, which is about 10 Km from the airport. The traveler may find it curious that practically any sign is written in two languages. One of them is obviously English and the other is Irish, a Celtic language. It is a complicated language. It is currently spoken by just over a million people (out of an estimated 4.5 million people in Ireland) and is taught in schools, although it is not actively used by young people. This is a sign of the strong patriotism that Irish people defend, as they refuse to lose their roots. Even so, the number of people who master this curious language is decreasing. In fact, Irish is considered an endangered language, surviving basically in the Republic of Ireland, while in Northern Ireland it is considered extinct. We glanced down at some of the prominent places and buildings of the Republican capital during our short journey for the left bank of the Liffey river to DART station, such as The Custom House (the Federal Government Office). Then we took the DART to our accommodation, and what was our surprise to know that the train ran along the Irish coast for much of the tour, giving us a beautiful view of the sea. We finished our first tour of Ireland in Dún Laoghaire (Dún Laoghaire-Ráth an Dúin in Irish), where we would stay during our stay in the Celtic country.

Dún Laoghaire is, possibly, a place to which the tourist or traveler does not pay too much attention unless he is staying in the city or its proximities. It is true that other places are more famous than this place. Still, it’s worth stopping for a few hours in this port city, an indisputable part of Ireland’s history, to see its museums, port and churches.

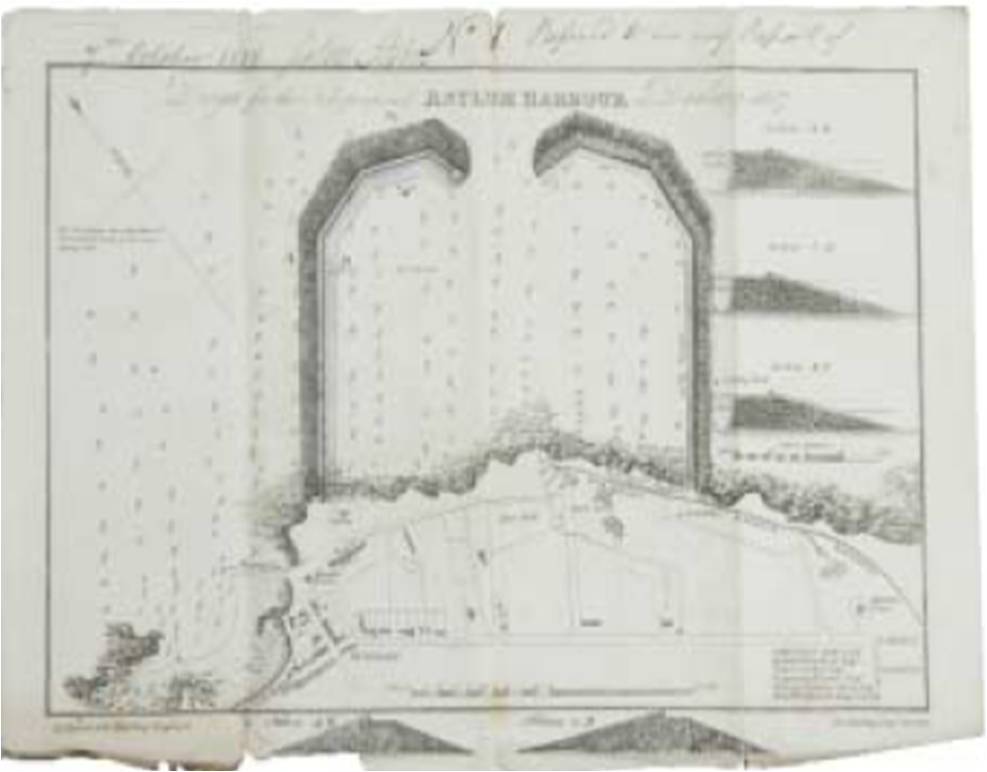

Etymologically, its name refers to Lóeguire mac Néill, Great King of Ireland converted to Christianity by Saint Patrick and who built a fortress in the 5th century, already disappeared. The first stone of its port was placed 201 years ago. In fact, last year was commemorated the bicentennial of the city. In the 17th century it was already frequented mainly by fishermen who had established a small settlement. They preferred the small dock of Dún Laoghaire because of the difficulties of access by the port of Dublin, due to a sand barrier in the mouth of the river Liffey which impeded the mooring of ships. While they waited for the right gusts of wind and tide level, they docked at Dún Laoghaire. In the 18th century trade began to take place on its coasts: several ships loaded with coal established the first commercial relations with the British coasts. The small town also gained a reputation for being cozy and having perfect beaches for bathing. Consequently, because of the problem of docking at Dublin Harbour and the increase in its popularity, the Irish Parliament made a petition to build the first quay, which would be supervised by General Charles Vallancey. However, the number of ships that needed to enter Dublin increased and the port remained dangerous. Therefore, at the beginning of the 18th century several projects were proposed to solve that problem. Among those projects was proposed to create a port in Dun Laoghaire. In fact, one of the designs was proposed by the Scottish master engineer John Rennie, famous for being the author of several canals (i.e. Avon Canal, Lancaster Canal, Royal Military Canal) and bridges (i.e. Waterloo Bridge, Southwark Bridge) and, ultimately, supervisor of the port works.

Even so, the authorities took their time to make their minds up. A tragedy finally made them to take action. In November 1807, two ships, the HMS Prince of Wales and the Rochdale, hit the rocks during a storm. About 400 people lost their lives. As expected, society mobilized to call for an urgent solution and avoid similar tragedies. Thus began the construction of the port of Dún Laoghaire, which would end up acquiring another breakwater and the shape it has today.

As already mentioned, the foundation stone was laid in 1817. Needless to say, the project attracted a number of workers and their families, laying the foundations for a prosperous future place to stay. In 1821, King George IV visited Ireland and departed from the port of Dún Laoghaire. As a tribute to this event, Dún Laoghaire and its port were renamed Kingstown, although its original name is still used today. In 1842, the port was considered finished when the first of the two lighthouses that now welcome to the interior of the port of Dún Laoghaire, located at the respective ends of the two breakwaters, was installed.

Since then, the port has had a great economic and warlike function, since from it have departed, sometimes not to return, ships with Irish soldiers to the Crimean War and the First World War among others. It is currently home to several yacht clubs.

Maritime Museum

Once the traveler has seen the port and enjoyed a pleasant walk through it, it is worth going into the interior of Dún Laoghaire. The first thing we find walking in the opposite direction of the harbour, and right in front of the DART stop, is the Rathdown-Dún Laoghaire County Council, the administrative centre of the county, whose capital is Dún Laoghaire. If we continue to the east through Queen’s Road, located next to the Town Hall, we will come across the Pavilion Theatre, one of the busiest places in this city from the opening of its doors in 1903 until the 60’s. In its indoors have come together thousands of people to enjoy plays and movies. Contemplating at its façade, it is difficult to imagine that the building was reduced to its ashes in two fires. But the truth is that little remains of its original structure. In the 1960s it began to decline. The culprit: an increasing number of families that had bought a television. Since then, its doors opened to offer some show or movie occasionally. Today, concerts, films, performances, representations, etc. can often be seen within its modern walls.

Continuing through Queen’s Road, we will arrive at dlrLexicon, a building that houses the cultural centre and central library of the city. Behind it we will see the façade of the Royal Marine Hotel, which formerly provided electricity to the aforementioned Pavilion Theatre.

However, the tower of a church that shyly protruded in a street across from Queen’s Road caught our attention. The church deserves a visit, as it is not just any church, since it houses the National Maritime Museum of Ireland. This church is known as the Mariners’ Church and was built in the first half of the 19th century to satisfy the spiritual needs of the growing number of sailors that docked at Dún Laoghaire.

At the museum, the traveler will learn and enjoy impressive collections about the Irish’s relationship with the sea. Navigation instruments, biographies of key figures in Irish history, naval weapons and much more can be enjoyed in this museum. Its entire collection is clearly imprinted with the footprints of courageous sailors who, on many occasions, lost their lives in order to bring food to their homes or to defend their land. For example, from the immense collection we could highlight the enormous lens that once belonged to the lighthouse Baily from Howth (to which the prolific Irish writer James Joyce made reference on more than one occasion in his most famous novel, Ulysses), whose light was equivalent to 2 million candles, or the diverse repertoire of bottled ships of all sizes. The museum also accepts personal objects that are related to the Irish maritime heritage. In addition, it has incunabula books and an invaluable archive of documents of Ireland’s history dating from the 18th century to the present day.

The traveler will also be able to obtain abundant data on the impressive Great Eastern, the largest steam liner in the world at the time it was launched (1858) and for the next 20 years. It was designed by engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunell and we imagine that it had not to be easy to build. Just take a look at its measurements: 211 meters long, 25 meters wide and a draft of between 6 and 9 meters. Slightly smaller than the famous Titanic. In fact, the first difficulty the engineers encountered was that they couldn’t find a dry dock to build that colossus. Finally, they had to build it along the Thames and throw it into the sea laterally. It could carry up to 4000 passengers without counting the crew and travel around the world without refueling. It seems that this transatlantic did not escape from that kind of curse that had the mania to harass many other great ships of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, since in its maiden voyage an explosion took the lives of several crew members, so its inauguration was delayed. It made several transatlantic voyages from the British Isles to America, although it was not very successful. Because of this and because its maintenance was expensive, it was withdrawn from this service. Later it was used to lay the first transatlantic submarine telegraph cable between Ireland and the United States in 1866 (in fact, the first transatlantic telegraph cable that was installed in the world). Not in vain, it was the only ship with the right dimensions to carry the necessary amount of cable. Its history ended sadly: in 1889 it was scrapped. Its parts ended up in the most unsuspected places. For instance, one of its masts (curious fact: this colossus of the seas had 6 masts that were named with the first 6 days of the week) ended up erected in the stadium of the Liverpool Football Club, in whose end today waves the flag of the club. Although everything that has been said may seem like a trifle in the eyes of the 21st century, it was a true feat of engineering in its time that could only be born of a brilliant mind such as Isambard’s. It even inspired another brilliant mind, Jules Verne, who took a trip in the Great Eastern, to write his novel A Floating City. Finally, it is worth mentioning some tragic stories, who knows if certain or not, that assure that during its dismantling the bodies of several workers who participated in the construction of the ship were found.

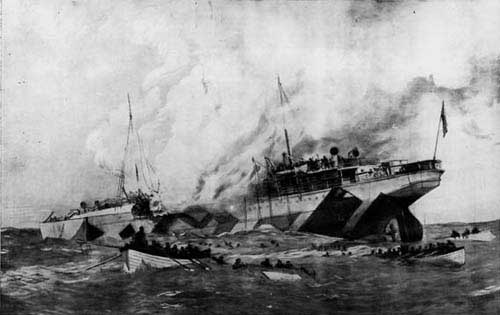

It is also worth giving some time to the exhibition on the centenary of the RMS Leinster, a well-known and tragic episode that happened a few leagues off the coast of Dún Laoghaire. On 10 October 1918, near the end of the First World War, a German submarine repeatedly torpedoed the ship as it was about to reach port until it sank. There were 771 people on it. Many died at the time of the sinking, others while trying to escape the voracious appetite of the ocean. The exhausted survivors managed to reach the port of Dún Laoghaire. It is not, therefore, an usual exposure, but a tribute to all those fallen in that tragedy perpetrated by that dark side of the human being that, unfortunately, makes its appearance on too many occasions. Various events (lectures, tours, etc.) accompany the exhibition for those who want to investigate this history.

Engraving of the tragic sinking of the RMS Leinster caused by two German torpedoes. The sinking of the RMS Leinster

Engraving of the tragic sinking of the RMS Leinster caused by two German torpedoes. The sinking of the RMS Leinster

A sculpture with a “turbulent” history

To rest from the excess of information and to integrate everything that has been seen in the museum, it is advisable to stop for a few minutes at Moran Park, adjacent to the cultural center. It takes its name from the Irish Republican Patrick Moran, who, according to his commemorative plaque at the entrance to the park, was a member of the Irish Republican Army, better known as IRA (but not the paramilitary organization famous for the various terrorist attacks it commited from its birth in 1969 until de 1990s. This group, that arose out of the Original IRA we are referring to, which led the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921), was known as the Provisional IRA). For this reason, he was executed in 1921 in Mountjoy prison. He was a member of The Forgotten Ten, ten members of the IRA who were executed in that prison. He was captain of the second battalion of company D of the IRA. He was accused of having participated in the Bloody Sunday of November 21, 1920, a terrible day to the history of Ireland in the context of the Irish War of Independence in which 32 people died between British and Irish. It all began when an IRA detachment mobilized under the orders of Michael Collins to assassinate some targets of the Cairo Gang group, a group of British intelligence agents infiltrated into Irish soil. IRA agents entered their targets’ homes in the morning and killed them off-guard in their sleep. In the afternoon of the same day, several military trucks and armoured cars stopped near a Gaelic football stadium, which at the time was overcrowded by a match. A crowd of men from the Irish police force (RIC; Royal Irish Constabulary) descended from those vehicles looking for the culprits of that morning’s murders. In a moment of confusion, the police opened fire on the public, causing several deaths and dozens of wounded. To this day, the reason why they started shooting at civilians is still unknown, although the authorities claimed that they were forced to do so because the IRA members they were chasing started the shooting first, although there is no solid evidence to support this version. Well, Moran was supposedly involved in that day, although he testified that he was in Blackrock, on the outskirts of Dublin. Finally, Moran and nine other revolutionaries were executed and buried under court-martial in unnamed graves in Mountjoy prison, in an attempt to make them forever forgotten. However, in 2001 the bodies were exhumed by their families to give them a Christian burial.

In this same park, in the north corner, stands a bronze sculpture worthy of admiration for its uniqueness. It is the sculpture of Christ the King. It is a triple cross showing three stages through which Jesus Christ passed in his last moments of life: a devastated Christ, physically and emotionally wounded, defeated, covered by a dark and sinister cloud; a renewed Christ, resurrected and recovered, with arms outstretched to console the humanity that betrayed him; and a majestic Christ, representing the victory of good. It was elaborated by the American sculptor descendant of Irish Andrew O’Connor and has a very “turbulent” history. The figure was actually ready in 1926, when the design was presented in a Paris salon. In 1931 a committee was founded to plan the installation of a sculpture in homage to Christ the King in Dún Laoghaire. The production of the sculpture was delayed because of the Second World War, for fear that the bronze could be used for the war. Finally, in 1951 it was taken to the city and installed in a temporary location. And it was temporary because the local priest opposed its placement, so the sculpture was removed. In 1978 it was installed almost definitively in Haigh Terrace and in 2014 it was installed in the place it occupies today, which hopefully will be the last.

The James Joyce Tower

If we extend our view beyond the Royal Marine Hotel and the adjacent shopping centre, we see the neo-gothic granite tower of St. Michael’s Church. Its beginnings almost coincide with the beginnings of the port of Dún Laoghaire in the 20s of XIX century. At first it was a humble church of small size. It grew thanks to the first priest of the parish, Bartholomew Sheridan, who also completed it in 1835. Over the following decades it underwent several reforms and between 1885-1902 the imposing tower was added. In 1965 the church suffered a fate similar to that of the Pavilion Theatre: a fire destroyed it, although fortunately the tower resisted the flames. Today, the church is an amalgam that mixes some of the remains of the old building with a more modern design.

Returning on our steps and continuing by Queen’s Road we will arrive at the most known park of Dún Laoghaire: People’s Park. It was built in Victorian style and it is opened since 1890. It still retains several classic tea rooms. Its two hectares allow the treveler to enjoy a peaceful tranquility. And if the traveler is looking for local produce, it’s a good idea to visit this park on the weekend, when several art, craft, book shopkeepers sell their products in the market. But this area also has reminiscences from the past. Opposite People’s Park there are two narrow streets: Rosmeen Gardens and Rosmeen Park. Well, in the middle of the Second World War, on December 20, 1940, two German bombs fell in these places, apparently without causing any victims, only structural damage. They were not the only cases, which is impressive given that Ireland was neutral at the time.

To end this first tour through the Emerald Isle, we head towards Sandycove, a suburb southeast of Dún Laoghaire. We can reach our destination through Scotsman’s Park, located just a few meters from People’s Park and that runs along the coast, to enjoy on the way some lovely views. At the end we will arrive at a tower of circular plant. It is known as Martello tower and was part of a network of towers along the coast built by the British to face the Napoleonic forces in the nineteenth century. Its name and structure comes from a 16th century tower located in Cape Mortella, Corsica. The English were impressed by its defensive quality during a siege of that tower in the context of the French Revolutionary Wars and decided to copy its design.

However, this tower has something special. Inside it houses a museum dedicated to one of the most important writers of history and to which we referred earlier: James Joyce. The museum was founded by the architect Michael Scott, considered one of the most important Irish architects of the 20th century and who bought the tower in 1954. He was also the architect of the building adjacent to the tower, Geragh Haus, which he used as his own house. Joyce, in fact, lived on the ground floor of that tower for a week in 1904 with two companions: Oliver St John Gogarty, a medical student and aspiring poet, and Samuel Chevenix Trench, a friend of the former and obsessed with Irish culture. However, a curious event forced Joyce to leave his residence in the Martello tower. Chevenix, who often had strange dreams, dreamed of a black panther. He woke up sweating and terrified and took his revolver in an attempt to put an end to the imaginary feline. To avoid a tragedy, his friend Gogarty tried to snatch his gun and two shots were fired. The young Joyce (in that moment he was 22 years old) left the tower terrified in order to not return. The event really impacted him, in fact he left it printed for eternity in the first pages of his novel Ulysses (1922), where he referred to the episode of the panther.

The traveler who visits the tower will find, among other things, the furniture that might have been there at the time of Joyce’s stay, the sculpture of a panther alluding to the curious event and, if you climb to the top of the tower, you will enjoy breathtaking views.

As a tribute to Joyce, every June since 1954, the Bloomsday festival (named after Ulysses’ protagonist Leopold Bloom) has been held free of charge in the Martello tower and surrounding areas. In this event, participants enjoy the same food as the fictitious characters and perform acts to represent some of the novel’s actions. That’s enough to make a visit to this legendary place.

This was our visit to Dún Laoghaire. Obviously, the city has much more history. It could be said that every square metre of Dún Laoghaire has its own history, but for reasons of space we are forced to summarise it. This place left us with a pleasant sensation that augured more intense experiences during the rest of our stay in Ireland. We can advance that it is impossible to prevent Ireland from being embedded in the traveler’s deepest entrails.

The next day we made an unforgettable excursion to Northern Ireland. If you want to continue discovering this incomparable island, go to the second part:

Ireland. Experiences in legendary lands (part 2). Crossing borders

In the third part we summarise the turbulent history of Ireland and visit Belfast. Join us!

Ireland. Experiences in legendary lands (part 3). Brief foray into the history of Ireland and visit to Belfast

REFERENCES

BBC (2014) John Rennie (1761 – 1821) [online] available in: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/rennie_john.shtml

Conghaile, P.Ó. (2015). Dublin Airport: Memories take flight as Ireland’s gateway celebrates 75 years. Independent [online] 19 June, available in: https://www.independent.ie/life/travel/ireland/dublin-airport-memories-take-flight-as-irelands-gateway-celebrates-75-years-30918318.html

Cowan, R. (2001) Dublin state funeral for IRA men. The Guardian[online] 15 October, available in: https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2001/oct/15/northernireland.ireland

Dún Laoghaire Harbour Company (2017) The Construction of Dún Laoghaire Harbour. Dublín: Dún Laoghaire Harbour Company [online] available in: http://dlharbour.ie/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/project_east_pier_construction.pdf

Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council (2018). People’s Park[online] available in: https://www.dlrcoco.ie/en/parks-outdoors/parks/peoples-park

Earth Observatory (2017). Topography of Ireland [online] available in: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/5343/topography-of-ireland

Engineers Journal (2018) The history of Dún Laoghaire Harbour – construction and compromise [online] available in: http://www.engineersjournal.ie/2018/01/09/history-dun-laoghaire-harbour-construction-compromise/

Government of Ireland (2009). Geography of Ireland [online] available in: https://web.archive.org/web/20091124012641/http://www.gov.ie/en/essays/geography.html

Islands (2010). Island directory tables [online] available in: http://islands.unep.ch/Tiarea.htm

James Joyce Tower & Museum (2018). James Joyce Tower & Museum[online] available in: http://www.joycetower.ie/

Johnston, W. (2001). Climate of Ireland, with maps [online] available in: http://www.wesleyjohnston.com/users/ireland/geography/climate.html

Lecane, P. (2005). Torpedoed! The RMS Leinster Disaster. Inglaterra: Periscope Publishing Ltd.

Lineman, H. (2016) “Christ the King” exhibition launches un Dún Laoghaire. The Irish Times [online] 1 June, available in: https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/christ-the-king-exhibition-launches-in-d%C3%BAn-laoghaire-1.2667830

Masa, A.P. (2005). El Great Eastern, un monstruo de los mares [online] available in: https://alpoma.net/tecob/?p=12280

Michael’s Church Dún Laoghaire (2018). Parish History [online] available in: https://www.dunlaoghaireparish.ie/component/content/article/12-parish-history/9-dun-laoghaire-parish-history

National Maritime Museum of Ireland (2016). National Maritime Museum of Ireland [online] available in: https://www.mariner.ie/museum/collections/

Pavilion Theatre (2014). History of Pavilion Theatre [online] available in: https://www.paviliontheatre.ie/about/history

Quigley, A.A. (1996) The day they bombed Dublin. The Irish Times[online] 1 June, available in: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/the-day-they-bombed-dublin-1.54917

RMS Leinster (2018). The Sinking [online] available in: http://www.rmsleinster.com/sinking/sinking.htm

Salminen, T. (1999). UNESCO Red Book of Endangered Languages: Europe [online] available in: http://www.helsinki.fi/~tasalmin/europe_report.html#IGaelic

Simons, Gary F. & Fennig, C.D. (2018). Irish [online] available in: https://www.ethnologue.com/language/gle

The Irish Story (2018). Today in Irish History, Bloody Sunday, 21 November 1920 [online] available in: http://www.theirishstory.com/2011/11/21/today-in-irish-history-bloody-sunday-november-21-1920/#.W5wac84za1s

Weather Online (2018). Ireland [online] available in: https://www.weatheronline.co.uk/reports/climate/Ireland.htm

Share this:

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Share on Bluesky (Opens in new window) Bluesky

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email